- About the Networks

- Apar Films

- Editorials

- Edgar Rice Burroughs Discussion Hour

- Gun for Henry

- Hell Hath No Fury

- I Hex

- Jason Rogers

- Joe Agent of V.A.T.

- Made-for-TR Movies

- Mr. Dot

- Mugger

- Mysterious Adventures

- Planet of the Nuns

- Saly Place

- TR Profile: Marty Phillips

- TR Profile: Ron Neilsen

- TR Profiles: Sam and Jack Rosen

- Tales of Mystery

- The Actor

- The Assassins

- The Christian Doherty Show

- The Fanatic

- The Fishboys

- The Magician of Horror

- The Sister

- The Swinger

- The West that Wasn't

- Voyage to the Stars

- Where Monsters Dwell

- Witch World

- Grab Bag of Shows

- A Word from Our Sponsor

Voyage to the Stars

I NEED A BUN

THE DECONSTRUCTION OF A VOYAGE

By Tom Soter

Alan Saly and I always felt a little bit frustrated by the creativity of Christian Doherty. Our colleague was so effortlessly imaginative but also so wild and illogical that we couldn't help but feel, "If we were in control, things would be different." I remember this feeling coming to a head on the 1972 Doherty-directed film called YOU MADE ME HATE MYSELF. The story made little sense, and Doherty – for some reason – let us take the film and redub it. Our logical additions may have improved it slightly, but they didn't add anything creatively. Our work was rather prosaic prose, while Doherty's was wild poetry.

Saly was the star of most of our major movies; but in the earlier, taped shows, he was a lesser light: a pronounced presence as a guest star and supporting player (his proper British butler Daggs on MUGGER was just one of his many accented roles; he played evil Grman scientists, southern sheriffs, and crotchedy old men; he seemed rarely to use his own voice). The irony was that the one show that was ostensibly about him, called SALY PLACE, featured Doherty as a character named Alan Saly who bore no resemblance to the real Alan.

The real Alan was (and is) an affable, kind, and brainy fellow: highly thoughtful, knowledgable, and, above all else, logical. A good writer, he was always very precise about his facts and his fiction. In his youth, he had a fondness for science fiction novels and short stories, especially those by Robert Heinlein and Isaac Asimov. Neither of these writers are great stylists but their ideas are terrific.

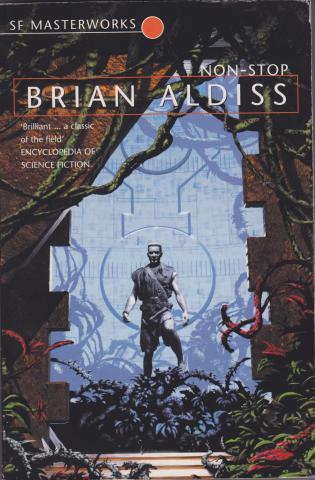

Brian Aldiss sci-fi classic: a prototype for VOYAGE?

VOYAGE TO THE STARS began in December 1970 as an Alan Saly production. Lifting its premise from any number of sci-fi novels, it tells the story of the starship Regulus, sent on a 50-year journey to the star Vega in the hope of finding more elbow room for an overpopulated earth. Already, this was more of a premise than most of our tape recorder plays had. Saly went even further: for most of the earliest episodes, he supplied plot synopses, sound effects (laser beams and explosions taped off of television), and even music from his favorite action shows (again taped off televison, mostly THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. and STAR TREK).

It all gave the series a unique feel, quite unlike the Doherty-dominated lunacy of our other shows. Contrast the pilot episode, "They Came from Beyond" – with Doherty in his only guest-starring role on VOYAGE - with later episodes like "Contact" or "Fateful Discovery," and you'll see the difference between a chocolate sundae and a hearty green salad. Unfortunately, that's the problem with much of the 12-episode series, produced from 1970-73: the inspired insanity of Doherty is more or less missing from the programs, which feature a patently absurd concept, ripe for mockery: as the ship encounters emergencies in space, the computer will awaken crewmen – only two or three per crisis – to deal with the situation.

This leads to a certain sameness, as Alan and I (with Tom Sinclair making a brief appearance in one episode), as the two principal players, are awakened at the start of each episode. We invariably try different accents (Alan is more successful than I am in this department, though he does gravitate towards Brits and Germans), but the dialogue is almost always the same, "Why were we awoken?" "It seems that...[plot premise]."

The stories are sci-fi standards, usually invoving alien races, ship malfunctions, or (our favorite), crewmen being driven mad by an outer space anomaly (an idea used in at least three episodes). The crewmen themselves are average joes (no women ever appear on the series), given to panicking, screaming for help, and screwing up right and left (one wonders how they were selected). Of course, no one tops Doherty's angry crewman Jameson in "They Came from Beyond." Bitter and argumentative ("God how I hate you," he says to his boss), he is leaving behind a wife and children for no explained reason (when asked why, he cries out in a melodramatic howl, "Because I HAD TO! GOD! I HAD TO!"), and implicitly threatens his superior when he is told they may have some interesting experiences on their journey ("O'Malley," he says, "I'd better not have any experiences"). The character is pure Doherty: wild, bizarre, and hugely entertaining.

One only wishes the rest of the series were as inspired. The storylines are well-thought-out but somewhat lackluster, with three exceptions: the brilliant "Jungles of Regulus," which features a well-developed plot, a great collection of music and effects, and two engaging characters (Alan as another Englishman and me in my Sam Rosen character, which was one of my best personas); and two deconstructionist later episodes of the series, "We're Selling Tombstones" and (my personal favorite) "Roger's Burial," Part 2.

I remember how "Tombstones" came about: we had 20 minutes before a TV show we were going to watch began; we decided to kill the time by throwing together a VOYAGE episode. Based partly on a DR. STRANGE comic, the episode was a non-stop, almost Doherty-like experiment in absurdity, as we free-associated our way through another crazy crewman/renegade computer scenario.

Things got even wilder in the penultimate episode of the series, "Roger's Burial," Part 2. The midsection in a trilogy about the ship's computer run amuck, this is 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY by way of GET SMART. It opens on earth, as Roger (Saly), the hero, goes in search of a scientist named Seltzman (Soter), 25,000 fathoms under water in the ocean's notorious Glomar Deep.

"Watch out there’s a rumor that a giant octopus is down there," a character says to Roger at one point, "but that’s only a silly rumor some sailor told me." Roger soon encounters the selfsame octopus, of course. Inside it, he discovers a man purporting to be Seltzman. (How they both get inside a giant Octopus and keep talking under water is never explained.)

"I’ve been in this Octopus for many moons now," says Seltzman.

"How can you tell?"

"I have a good watch."

But Roger catches him out: "Seltzman had lunaphobia. He had a crazy mixed up fear of the moon, he would never mention the moon in a sentence. You're not Seltzman. You’re a gemini construct of the computer."

Logical, like the old VOYAGE, but now with a twist: the construct ate Seltzman's brain, so – in order to obtain the knowledge necessary to save the day, Roger (and his friend Fred) decide they must eat the construct's brain, because, as Roger explains, "Your brain must have absorbed some of his knowledge, because when tapeworms are fed to one another they absorb the ability to go toward light or away from light as shown in the scientific experiments of Dr. Cholestoral."

They dig in, with Roger saying, "This tastes good!" and Fred exclaiming, "I need a bun!"

So, in the end, we became what we had fought against: absurdity, warped logic, inspired lunacy. In short, Dohertyesque.

Works for me.

Listen to:

They Came From Beyond

Episode 1 Taped: 1970

With the earth overpopulated, the starship Regulus begins a 50-year journey to a distant star in the hopes of colonizing it. But the journey may face trouble from a bitter crewman who hates computers. Jameson: Adolph Etler. O’Malley: Alan Saly.

The Collectors

Episode 4 Taped: March 29, 1971

Jackson and Trask encounter a gigantic spaceship that is slowly pulling the Regulus inside it. Jackson: Tom Soter. Trask: Alan Saly.

The Jungles of Regulus

Episode 5. Taped: March 29, 1971

In a rare dramatic role, Sam Rosen plays Carl Harper, a weapons expert, who teams up with Jake Bush to deal with a strange growth that is threatening the existence of the starship. Bush: Alan Saly.

A Touch of Treachery

Episode 7. Taped: September 10, 1971.

In the second season opener, the Regulus encounters an alien probe that transforms two of the crewmen into madmen set on ruling the ship. George Silverman: Alan Saly. Jonathan Rollins: Tom Soter.

Roger's Burial, Part 2

Episode 11. Taped: January 25, 1973

In the second of three parts, a renegade computer threatens the starship Regulus, as scientists on earth seek a solution. Roger: Bill Hamer.